Threaded bottom brackets aren’t the solution you think they are

Whether threaded or press-fit, the real issue when it comes to bottom bracket longevity is poor frame tolerances.

I’ve been around long enough to witness firsthand how bikes went from from cup-and-cone bottom brackets to cartridge ones, from square-tapered to thru-shafts, from threaded shells to all manner of press-fit ones, and then finally back to threaded again. All of these changes were ostensibly made in the name of technological progress: lighter, stiffer, more durable, and so on. Was it always entirely a forward progression? Not exactly.

The switch back from press-fit to threaded was largely due to market backlash. Press-fit bottom brackets were claimed to provide better performance than threaded ones, but there were so many complaints about them being a pain to work on, prone to creaking, and quick to wear out that the industry had little choice but to backtrack.

All of these things were true to some extent. However, none of them are fundamentally tied to using press-fit cups instead of threaded ones. And unfortunately, while we may have made it a little easier to work on stuff with the switch back to threaded, we haven’t actually solved anything.

We’ve just moved the problems around.

The promise of threaded

Many riders prefer threaded bottom bracket shells for a number of reasons.

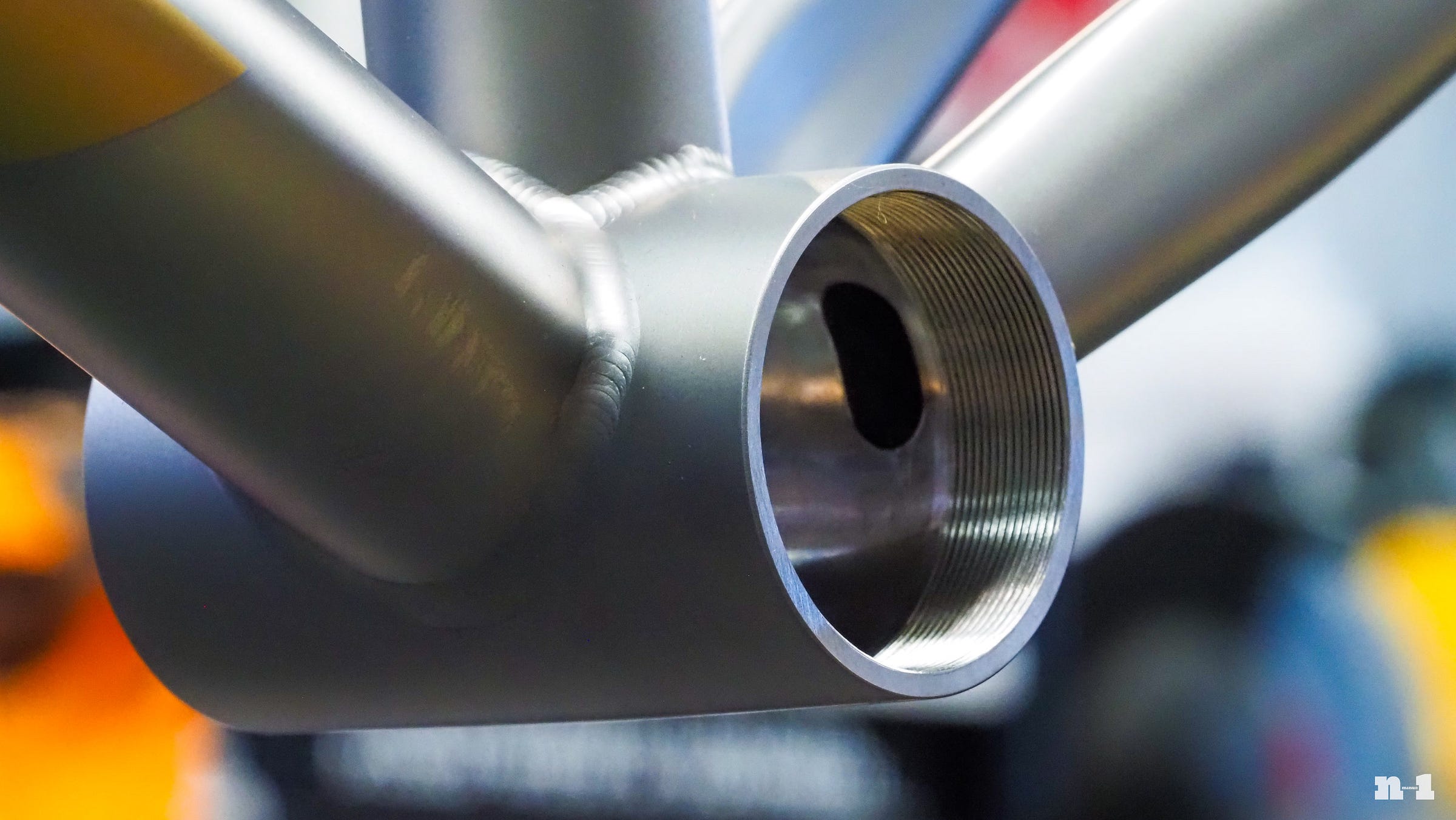

For one, plenty of mechanics – both home and professional – find them more straightforward to work on. Threaded cups don’t require flared punches and hammers, a variety of presses, or a witch’s brew of adhesives and solvents to install or remove them. As long as you’ve got the correct tool and some leverage, you’re good to go (never mind the eight billion different spline tools for threaded cups, but that’s a topic for another day).

Threaded shells are also often better for the bearing cartridges themselves. Press-fit shells on all-too-many mass-produced carbon fiber frames are too thin or insufficiently round, which either doesn’t provide enough structural support to keep the bearings from moving around (which can result in creaking) or creates point stresses on the bearing (which can lead to premature bearing wear).

In contrast, threaded cups are almost always made of relatively thick-walled aluminum and turned on a lathe. The bearings are not only more likely to press evenly into the cups with just the right interference-type fit, but they’re also more likely to stay that way after the cup is installed in the frame.

Creaks are usually easier to fix, too. Bottom bracket creaks typically occur when you get sudden micro-movements between the cups and the shell under load. With press-fit cups, you were limited to various adhesive compounds or switching to a thread-together design that could be secured more tightly inside the frame. But with threaded shells, oftentimes all you have to do is remove the cups, clean and regrease the threads, and then reinstall to the proper torque. Even challenging cases can often be resolved with just PTFE tape or mild thread retainer.

All in all, most folks just find threaded shells to be easier to live with. But even so, it’s not like all of the old issues have suddenly gone away entirely. We’ve now come full circle, but our bottom brackets are still wearing out too quickly, they’re still creaking, and we’re still annoyed.

It’s all about the alignment

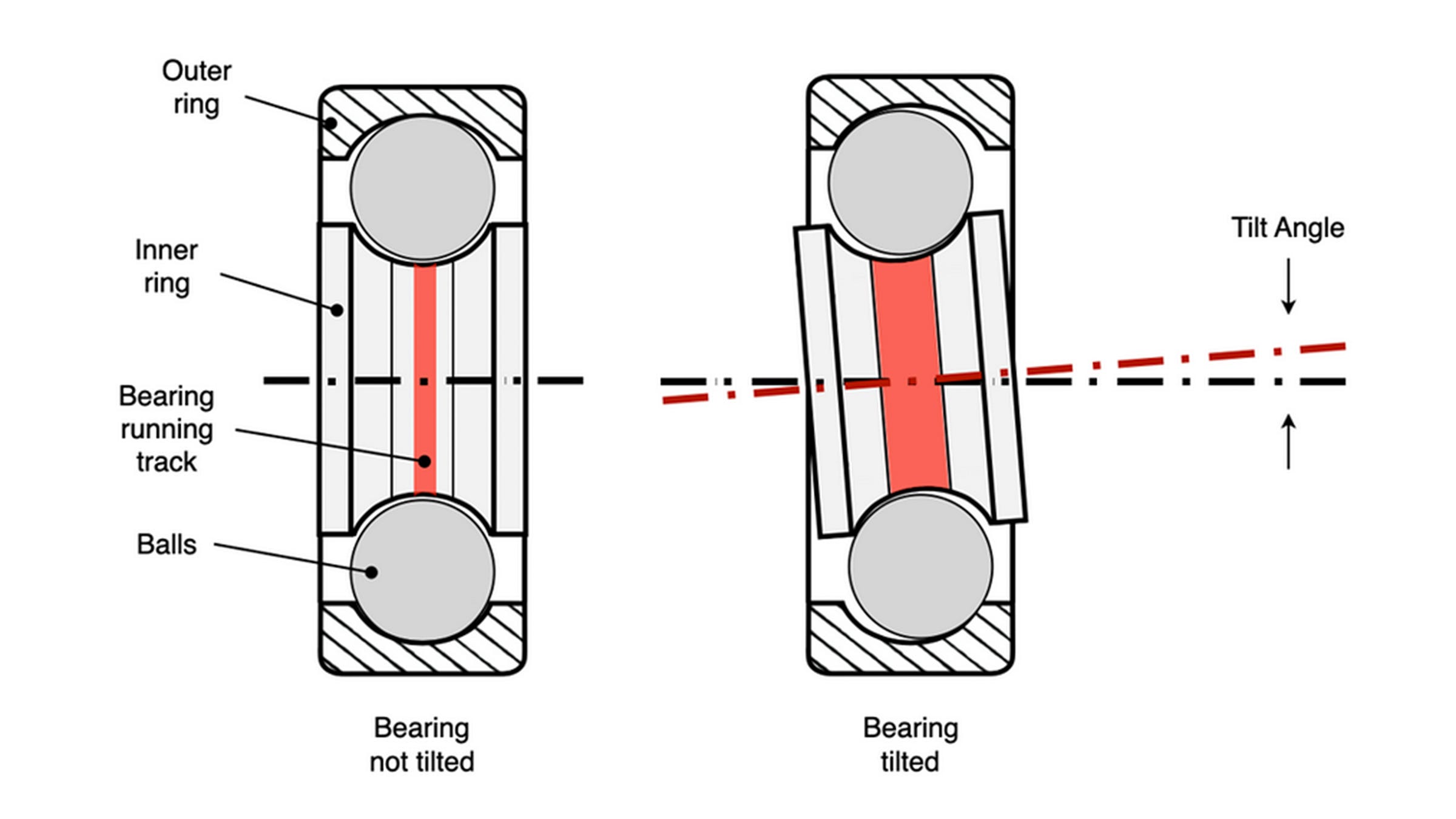

Fundamentally, a bottom bracket is a rigid shaft rotating within two bearings, and while there are various well-established engineering guidelines for such a system (bearing spacing, bearing size, bearing bore tolerances, and so on), there are basic dimensional features that is consistent no matter what: those two bearings should be both parallel and concentric to each other.

If they’re not – even by a little bit – each bearing is constantly subjected to loads they’re not designed to endure, which dramatically shortens its lifespan.

“The amount of misalignment a bearing can tolerate is called the free angle of misalignment,” explained Matt Harvey of Enduro Bearings. “How much misalignment the radial bearing can manage without accelerating fatigue and friction is based on several factors, the important ones being internal clearance and ball diameter. The more initial internal clearance the bearing was produced with, the slightly more misalignment the bearing can handle.

"Pre-load rings and systems on cranks are ubiquitous now, and in general, we are pre-loading radial bearings that are not really designed for it,” he continued. “Radial bearings are designed to have play where the balls on the bottom are momentarily carrying all of the load, then sort of floating over the top. While lightly preloading small radial bearings is alright, the alignment needs to be very good to get performance and life. When you preload radial or angular contact bearings, all of the balls are engaged and carrying the load throughout the rotation. If you have misalignment, there may be a point where a smaller ball cannot roll through the tight point and it will skid, cutting the metal of the bearing races and accelerating wear.”

These sorts of misalignments were the core issue with most problematic press-fit bottom bracket shells, not that they were press-fit, period. While some brands (like Giant and Pivot, for example) have been able to do press-fit well, too many brands couldn’t figure out how (or didn’t care) to manufacture the shells with sufficiently tight dimensional tolerances. Instead of being perfectly cylindrical bores of a very specific diameter and depth, press-fit shells were often oversized or undersized – or just not quite round.

Moreover, frames built with one-piece threaded shells are more likely to be cylindrical throughout the whole length, but higher-end frames that prioritize low weight instead often use two separate rings that have to be aligned to each other within a larger surrounding composite structure. And not surprisingly, getting that alignment right isn’t exactly easy.

While switching to threads makes some things better, it doesn’t automatically solve that core issue of alignment – and in fact, it can actually make it worse in some cases. Is there any reason to expect that companies that did press-fit poorly will suddenly do threaded shells well? I wouldn’t take it as a given.

“I like threaded stuff because you can put it in, tighten it down, adjust it, and it stays put provided everything is faced and smooth and bottoming out correctly,” said Jim Potter, owner of Vecchio’s Bicicletteria in Boulder, Colorado. “But more often than not, frames are not properly faced from the factory. You put the tool in and start facing, and after just a few turns, you notice that only half of the shell is being cut so no, they’re not square. And it’s usually the same thing on the other side. Sometimes I start cutting into the metal on one edge before I start cutting into the paint on the opposite edge. It’s very common.”

The problem with press-fit was the execution, not the concept

One of the interesting things about threaded bottom bracket shells is that if you look elsewhere on your bike, you won’t find any other threaded bearing fitments.

Headsets? Those either have press-fit cups or drop-in bearings. Hubs? While there are some exceptions, nearly all modern hubs these days use press-fit bearings. Rear derailleur pulley wheels? Press-fit. The bearings in your suspension pivots? Press-fit, each and every one of them.

In fact, virtually every single industrial bearing-and-shaft system uses bearings that are press-fit directly into a part, instead of being press-fit into a sub-assembly that’s then threaded into that part.

Why? When it comes to ensuring proper bearing alignment, press-fit is the norm because boring two holes is a more reliable way to locate bearings. But with a threaded bottom bracket, you’re introducing at least one additional interface, which increases the likelihood for tolerance stack-up and misalignment. So yes, that means that at least in theory, even press-fit cups should be better than threaded ones, even though you’re still introducing one additional interface than you really need.

Is threaded easier to work on? Sure. But from a pure engineering standpoint, it also makes it easier to get it wrong.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to n-1 to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.